Global Warming

I’ve started to be one of those environmental nuts who spouts wild claims like “society will collapse within 12 years” and “all life on Earth could go extinct.” I’m creating this post to track my sources and discuss how I think we should respond to the situation.

You guys remember that one time in 1992 when 1,700 scientists gave their signatures to warn humanity of an impending global disaster brought on by climate change? When they said, “Our massive tampering with the world’s interdependent web of life—coupled with the environmental damage inflicted by deforestation, species loss, and climate change—could trigger widespread adverse effects, including unpredictable collapses of critical biological systems whose interactions and dynamics we only imperfectly understand.”?

Remember 25 years later in 2017 when more scientists issued a second warning?

World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice 12, December 2017

“Twenty-five years ago, the Union of Concerned Scientists and more than 1700 independent scientists, including the majority of living Nobel laureates in the sciences, penned the 1992 “World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity”…They expressed concern about current, impending, or potential damage on planet Earth involving ozone depletion, freshwater availability, marine life depletion, ocean dead zones, forest loss, biodiversity destruction, climate change, and continued human population growth.

The authors of the 1992 declaration feared that humanity was pushing Earth’s ecosystems beyond their capacities to support the web of life. They described how we are fast approaching many of the limits of what the biosphere can tolerate without substantial and irreversible harm. The scientists pleaded that we stabilize the human population, describing how our large numbers—swelled by another 2 billion people since 1992, a 35 percent increase—exert stresses on Earth that can overwhelm other efforts to realize a sustainable future (Crist et al. 2017). They implored that we cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and phase out fossil fuels, reduce deforestation, and reverse the trend of collapsing biodiversity.

On the twenty-fifth anniversary of their call, we look back at their warning and evaluate the human response by exploring available time-series data. Since 1992, with the exception of stabilizing the stratospheric ozone layer, humanity has failed to make sufficient progress in generally solving these foreseen environmental challenges, and alarmingly, most of them are getting far worse…”

Yeah…

A paper by climate scientist Jem Bendell heavily influenced me. I gave a talk at my local philosophy club on the issue with a write up I include below.

The Role of Philosophers in the Face of Climate Change

Elliott Collin Ploutz Philosophy Club - 3/28/19

An academic paper recently made headlines for having over 100,000 downloads by the general public. The article, Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy, by professor Jem Bendell is the result of Dr. Bendell’s 2017 -2018 sabbatical spent reviewing current climate science. His conclusion is bleak - we likely only have 10-12 more years before society breaks down due to harsh conditions. Dr. Bendell states,

“I am aware that some people consider statements from academics that we now face inevitable near-term social collapse to be irresponsible due to the potential impact that may have on the motivation or mental health of people reading such statements. My research and engagement in dialogue on this topic, some of which I will outline in this paper, leads me to conclude the exact opposite. It is a responsible act to communicate this analysis now and invite people to support each other, myself included, in exploring the implications, including the psychological and spiritual implications.”

In our discussion, I will briefly explore the evidence for catastrophic climate change, the types of climate change denial, and most saliently what the role of philosophers is in the face of human extinction.

Evidence

The following is taken from the section “Our Non-Linear World”2, “In this section I summarise the findings to establish the premise that it is time we consider the implications of it being too late to avert a global environmental catastrophe in the lifetimes of people alive today.”

The simple evidence of global ambient temperature rise is undisputable. Seventeen of the 18 warmest years in the 136-year record all have occurred since 2001, and global temperatures have increased by 0.9°C since 1880 (NASA/GISS, 2018). The most surprising warming is in the Arctic, where the 2016 land surface temperature was 2.0°C above the 1981-2010 average, breaking the previous records of 2007, 2011, and 2015 by 0.8°C, representing a 3.5°C increase since the record began in 1900 (AaronMorrison et al, 2017). Non-linear changes are of central importance to understanding climate change, as they suggest both that impacts will be far more rapid and severe than predictions based on linear projections and that the changes no longer correlate with the rate of anthropogenic carbon emissions. In other words - ‘runaway climate change.’ That means we could remove a quarter of the cumulative CO2 emissions of the last three decades and it would already be outweighed by the loss of the reflective power of Arctic sea ice. One of the most eminent climate scientists in the world, Peter Wadhams, believes an ice-free Arctic will occur one summer in the next few years and that it will likely increase by 50% the warming caused by the CO2 produced by human activity (Wadhams, 2016). The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) reports that weather abnormalities related to climate change are costing billions of dollars a year, and growing exponentially. For now, the impact is calculated in money, but the nutritional implications are key (FAO, 2018). About half of the world’s coral reefs have died in the last 30 years, due to a mixture of reasons though higher water temperatures and acidification due to higher CO2 concentrations in ocean water being key (Phys.org, 2018).

“The impacts I just summarised are already upon us and even without increasing their severity they will nevertheless increase their impacts on our ecosystems, soils, seas and our societies over time. It is difficult to predict future impacts. But it is more difficult not to predict them. Because the reported impacts today are at the very worst end of predictions being made in the early 1990s…”

“So, we are not on the path to prevent going over 2 degrees warming through emissions reductions. In any case the IPCC estimate of a carbon budget was controversial with many scientists who estimated that existing CO2 in the atmosphere should already produce global ambient temperature rises over 5°C and so there is no carbon budget – it has already been overspent (Wasdell, 2015).

That situation is why some experts have argued for more work on removing carbon from the atmosphere with machines. Unfortunately, the current technology needs to be scaled by a factor of 2 million within 2 years, all powered by renewables, alongside massive emission cuts, to reduce the amount of heating already locked into the system (Wadhams, 2018).”

“Clearly a massive campaign and policy agenda to transform agriculture and restore ecosystems globally is needed right now. It will be a huge undertaking, undoing 60 years of developments in world agriculture. In addition, it means the conservation of our existing wetlands and forests must suddenly become successful, after decades of failure across lands outside of geographically limited nature reserves. Even if such will emerges immediately, the heating and instability already locked into the climate will cause damage to ecosystems, so it will be difficult for such approaches to curb the global atmospheric carbon level. The reality that we have progressed too far already to avert disruptions to ecosystems is highlighted by the finding that if CO2 removal from the atmosphere could work at scale, it would not prevent massive damage to marine life, which is locked in for many years due to acidification from the dissolving of CO2 in the oceans (Mathesius et al, 2015).”

“That report of subsea permafrost destabilisation in the East Siberian Arctic sea shelf, the latest unprecedented temperatures in the Arctic, and the data in non-linear rises in high-atmosphere methane levels, combine to make it feel like we are about to play Russian Roulette with the entire human race, with already two bullets loaded. Nothing is certain. But it is sobering that humanity has arrived at a situation of our own making where we now debate the strength of analyses of our near-term extinction.”

“We do not know for certain how disruptive the impacts of climate change will be or where will be most affected, especially as economic and social systems will respond in complex ways. But the evidence is mounting that the impacts will be catastrophic to our livelihoods and the societies that we live within. Our norms of behaviour, that we call our “civilisation,” may also degrade. When we contemplate this possibility, it can seem abstract. The words I ended the previous paragraph with may seem, subconsciously at least, to be describing a situation to feel sorry about as we witness scenes on TV or online. But when I say starvation, destruction, migration, disease and war, I mean in your own life. With the power down, soon you wouldn’t have water coming out of your tap. You will depend on your neighbours for food and some warmth. You will become malnourished. You won’t know whether to stay or go. You will fear being violently killed before starving to death.”

There was at one time a debate of whether or not humans contributed to the Earth’s heating, but our certainty has reached a “gold standard,” “…confidence that human activities were raising the heat at the Earth’s surface had reached a “five-sigma” level, a statistical gauge meaning there is only a one-in-a-million chance that the signal would appear if there was no warming.”

Denial

“There are three main factors that could be encouraging professional environmentalists in their denial that our societies will collapse in the nearterm.”

- Scientific reticence - “Using the case study of sea level rise, he threw light on processes that lead to “scientific reticence” to conclude and communicate scenarios that would be disturbing to employers, funders, governments and the public (Hansen, 2007). A more detailed study of this process across issues and institutions found that climate-change scientists routinely underestimate impacts “by erring on the side of least drama” - (Brysse et al, 2013). Combined with the norms of scientific analysis and reporting to be cautious and avoid bombast, and the time it takes to fund, research, produce and publish peer-reviewed scientific studies, this means that the information available to environmental professionals about the state of the climate is not as frightening as it could be. In this paper I have had to mix information from peer-reviewed articles with recent data from individual scientists and their research institutions to provide the evidence which suggests we are now in a non-linear situation of climactic changes and effects.”

- Human psychology on climate change - “These personal processes [preserving the status quo] are likely made worse for sustainability experts than the general public, given the typical allegiance of professionals to incumbent social structures. Research has revealed that people who have a higher level of formal education are more supportive of the existing social and economic systems that those that have less education (Schmidt, 2000).”

- Institutional - “I have worked for over 20 years within or with organisations working on the sustainability agenda, in non-profit, private and governmental sectors. In none of these sectors is there an obvious institutional self-interest in articulating the probability or inevitability of social collapse. Not to members of your charity, not to consumers of your product, not to voters for your party. There are a few niche companies that benefit from a collapse discourse leading some people to seek to prepare by buying their products…But the internal culture of environmental groups remains strongly in favour of appearing effective, even when decades of investment and campaigning have not produced a net positive outcome on climate, ecosystems or many specific species.”

Dr. Bendell concludes with the Deep Adaptation Agenda: Resilience asks us “how do we keep what we really want to keep?” Relinquishment asks us “what do we need to let go of in order to not make matters worse?” Restoration asks us “what can we bring back to help us with the coming difficulties and tragedies?”

“This assessment that we face near-term human extinction can draw on the conclusions by geologists that the last mass extinction of life on earth, where 95% of species disappeared, was due to methane-induced rapid warming of the atmosphere (Lee, 2014; Brand et al, 2016).”

- The Deceiver

- The Deceived

- The Self-Deceived

- The Skeptic

- The Truly Ignorant

The current administration is actively suppressing climate research. The administration released one of the largest American climate reports on Black Friday. “However, several [researchers] noted that the timing of its release, at 2 p.m. the day after Thanksgiving, appeared designed to minimize its public impact.”

Philosophers

What should we do about this?

Traits western philosophers tend to share:

- Rationally and scientifically minded

- Motivated by truth and wisdom

- Rigorous understanding of cognitive biases and logical fallacies

There are a host of cognitive biases and logical fallacies which can orient the average person to disregard the notion of societal collapse due to climate change. As one journalist, David Wallace-Wales puts it:

“We build our view of the universe outward from our own experience, a reflexive tendency that surely shapes our ability to comprehend genuinely existential threats to the species. We have a tendency to wait for others to act, rather than acting ourselves; a preference for the present situation; a disinclination to change things; and an excess of confidence that we can change things easily, should we need to, no matter the scale. We can’t see anything but through cataracts of self-deception.

The sum total of these biases is what makes climate change something the ecological theorist Timothy Morton calls a “hyperobject” — a conceptual fact so large and complex that it can never be properly comprehended…That climate change touches so many of our cognitive biases is a mark of just how big it is and how much about human life it touches, which is to say, nearly everything.”

Philosophers are supposed to be the experts here! If we want our species and the current biosphere to flourish, we must act.

Authors have preached extinction is nigh for thousands of years, but we now have more evidence for the thesis.

A Year of Deep Adaptation Posted by jembendell on July 7, 2019

Working with my colleague Matthew Slater, I have produced a Compendium of Research Reports on Climate Chaos and Impacts, which we release today. In it I summarise 23 studies which I consider key from the past 12 months. Last year it was unusual to claim that it is too late to stop runaway climate change damaging our agriculture to such an extent that it will lead to the breakdown of our societies within the next ten years. However, the key takeaway from this Compendium of research is that there is now a wider range of peer-reviewed dots to draw from in order to arrive at that perspective. However, there are not many mainstream researchers joining all those dots, to offer conclusions and predictions for human society. The difficulty is that researchers exist in academic silos, such as climate modelling on the one hand, agronomy on the other, or migration on the other, and a belief in the meaningfulness of silos is at the core of what gives us a sense of self-esteem and confidence for expressing our views. To move beyond drawing dots, to joining those dots, requires an ability to understand multiple fields of scholarship, their methods and limitations, which is a challenging skill set and time-intensive process.

Then there are some people who have worked on environmental issues for some time and have portrayed my analysis as suggesting that we give up on the drawdown and cutting of carbon; which I do not. When people say “we need hope” they might be expressing their assumption that they themselves need a pleasant story of the future in order to avoid their own emotional pain – and avoid witnessing it in others. Fortunately, I have discovered this past year that the loss of a hope that we can reform to maintain our way of life has been shocking people into waking up to not only to our environmental predicament but also the reality of impermanence and death. That means they engage in the present moment with a passion for truth and love. In general all of the criticisms I have heard fall into one of the forms of denial that I wrote about last year.

Meanwhile, some other commentators have agreed with the general analysis that we face imminent collapse, but have questioned how certain we can be, or when it will happen. I think it is important to stay aware of the latest data and revise what we think will happen. I also think it is important to consider how we explain our views to different audiences…People may want to avoid believing societal collapse is inevitable in order to provide themselves with a psychological escape, so that they can still hope that someone or something will stop it happening somehow. Looking at the current climactic changes, the rising emissions and habitat destruction, the biological impacts, the warming feedbacks, the agricultural impacts, the slowness of response, the intransigence of capitalism and its client politicians, and the cultural dependence on ideas of progress and control, and the rise of stories of blame that avoid reality and foster ignorance and hate, I think that “inevitable” societal collapse is a more accurate way of communicating my view that it is now unavoidable, than saying collapse is likely or near certain. I am aware that some people challenge us to recognise that societal collapse is already underway but unevenly distributed. The recent statement from the UN on this matter is a sober reminder that millions have already suffered terribly from climate chaos.

Since the paper came out, I have come to consider a new reason why societal collapse is inevitable. It came to me when I spoke at the European Commission. During my talk I did a quick poll to discover that about 90 percent of the officials in the room believed that collapse is coming within their lifetimes. Yet their ability to conceive of what was appropriate to discuss as policy responses and activism was, in general, woeful. The ideas being shared were more of the same tinkering with capitalism and redirecting private investment into mitigation efforts. Why? One hypothesis is that the highest have the farthest to fall. If one is well-respected, well-paid, and living well in the current system, perhaps with a sense of responsibility for lots of employees and stakeholders, then one has the most to let go of in order to allow the full impact of our current situation to sink in. At a sub-conscious level it eats away at assumptions you didn’t know you had. For instance, assuming that one would be respected by your children and younger generations as you enter old age, and, ultimately as you lie on your death bed. To be successful in society means one is having affirmed, daily, the illusion of the socially-respected agentic separate Self. Instead, our climate chaos invites us to see that we aren’t separate, we aren’t in control and our stories of self-respect and meaning were always made up. We must let our deepest assumptions and stories melt away to find what else can emerge. That may be why I have a better time talking to children about collapse than I do talking to people with senior jobs.

Many people ask me about when a societal collapse is likely. As I explained in the paper, I do not know, but guess that within 10 years that it will be occurring in many, perhaps most, countries of the world. Some have argued it could occur more quickly. As I explained above, some argue that it has already started in some countries. This question about the timing of collapse is an understandable one, given that it affects our assessment of what to focus on. Given the uncertainty of prediction in complex systems, to avoid putting a date on predictions is justifiable. The direction is clear but the speed of it less so. For instance, I know I am going to die, but, because I have no interest in killing myself, nor have a terminal diagnosis, I do not know when I am going to die. The problem I have with the argument that I should not give a time horizon like 10 years is that not deciding on a time horizon acts as a psychological escape from facing our predicament. If we can push this problem out into 2040 or 2050, it somehow feels less pressing. Yet, look around. Already harvests are failing because of weather made worse by climate change. So, a year after my paper came out, I am still guessing that the society I will be living in, whether the UK or elsewhere, will have collapsed within 9 years. It could be sooner. I hope to help slow things down by bringing attention to our predicament and promoting adaptation.

In the original paper I did not explain fully what I mean by societal collapse, nor did I go into the mechanisms by which it might occur. Therefore, I did not explore how it could be slowed or softened. By societal collapse I mean “the uneven ending of our current means of sustenance, shelter, security, pleasure, identity and meaning. Others may prefer the term societal breakdown when referring to the same process.” My theory is that multi-breadbasket failure across the northern hemisphere, combined with location-specific damage to other harvests, will disrupt our societies within 9 years, due to the impact on food prices and food supplies. I also predict that water shortages will trigger migration and conflict, thus making collapse more likely in some countries. I warn that the reactions of our financial system may precipitate collapse ahead of the shortages of food and water or the movements of populations. The psychological impacts of the increasing economic, societal and political turbulence may also trigger disturbances, which could manifest through civil unrest or political extremism. I respect those who believe these processes are already underway. Clearly there is more analysis needed on these possibilities, and I have been encouraging people in food security, disaster risk reduction, human security and related fields to explore these questions.

Climate Change - Why we are heading for extinction and what to do about it

Published on May 26, 2018

Roger Hallam is co-founder of the Radical Think Tank. His PhD studies looked at protest movements and revolutionary campaigns and what factors make them successful.

He assumes only three core premises:

- 2 + 2 (simple arithmetic)

- Consistency (no contradictions)

- The world is real (there is an external world)

We are currently at 1.2 degrees Celsius of warming. The Paris Agreement assumes we can extract carbon from the atmosphere to keep warming under 2 degrees globally. However, we don’t yet have scale-able technology to do this. We’re expecting 0.5C of warming in the next 10-20 years.

Much of the CO2 locked into the system is in the ocean. Once the polar ice melts, we can expect another 0.5C warming. With less ice reflecting sunlight, the oceans will become warmer as they absorb heat.

We’re already locked into 1.2C + 0.5C + 0.5C = 2.2C.

This is ignoring other variables that could contribute to warming and prediction which suggest 8C of warming in the next 10 years. However, as the ocean heats up, water vapor is expected to add another 1C of warming, so we’re at 3.2C.

Between 2.5C and 3.5C rain forests are expected to burn down, adding 1.5C.

This puts us at 4.7C of warming assuming average temperature increases.

Based on physics, centers of continents warm faster than the coastal areas. The issue is at 4C of warming we can’t grow grain in the center of continents.

We’re looking at all of this in the next 10-15 years.

There were 5 major extinctions in the historical record. One was caused by a meteor, the rest was caused by C02 (volcanoes) and methane build up in the atmosphere.

From the record, at 12.5C all of the ice at the poles melt. At 23C, the paleo record shows 95% of life on Earth dies. When there is no polar ice, there’s no wind. The ocean becomes more still and stagnant, then nitrate-sulfate is released from the ocean. The atmosphere becomes poisonous for mammals, but some reptiles might get away. At 6C, phyto-plankton which produce oxygen die, changing the concentration of oxygen in the air further. This is why higher-level mammals die.

He’s talking about 4 certain additions in warming, but there are 69 factors that could lead to warming. One is the release of methane trapped in the permafrost. If 1% of the methane is released, that could add 0.5C, and that can happen in a year. This is probabilistic, but 4C is supported by “basic physics.”

We’re at a point where we know human action is going to cause mass-death and possibly extinction.

“If a government is intending to kill the livelihood of its citizens, you don’t have a right to rebel, you have a duty to rebel.” - John Locke

Since the 90’s, carbon emissions have gone up 60% despite all efforts to reduce them.

He argues based on previous research only about 3-5% of people will be activated to activism and most others will be pushed to defeatism.

Civil disobedience like a street protest with 1 million individuals equates to 1,000 arrests or 500 jailed. If you can get people to go to prison, this will actually disrupt the system. Analyzing the civil rights movement of Martin Luther King Jr., 5,000 people jailed led to policy change. His estimate is 1,000 people imprisoned in prison can affect policy. This is simplistic, but we know the number needed to be imprisoned is lower than we think.

There’s a backfire effect when we see members of our group terribly oppressed by the dominant power. Through sympathy, others who would’ve been mobilized do not. Sometimes this also activates many who were unsure but become activated. We can’t predict which way things will go but to try and see.

He argues for psychological motivation. Many ardent activists are religious rather than rational. He argues this comes from action based on duty independent of the outcome. We tend to need a reason, but for people to mobilize, we need to ask questions about duty, honor, responsibility, and what it means to be a good person.

How to Enjoy the End of the World by Professor Sid Smith

Published on Apr 23, 2019

This lecture had a profound effect on me because of the mathematical and intuitive explanation. He analyzes organisms, societies, and planets based on physics models of energy.

A dissipative structure is embodied energy that takes in exergy (low entropy energy) and expels heat (high entropy energy), according to the arrow of time (tending towards entropy). For instance, a fire is a dissipative structure. The fire uses fuel (exergy) to maintain and grow until the fuel is used. Once the fuel is gone, all exergy has been released as heat. The energy is the same, but the exergy is gone. “One can view the entire universe as a dissipative structure. The big bang released exergy, creating time and space. The feature that is perhaps most characteristic of dissipative structure, including the universe itself, is complexity.”

Complexity appears to defy the second law of physics, which is in a closed system entropy will always increase. “Order is never spontaneously produced from disorder. Once a glass breaks, you can’t un-break it.” Every dissipative structure converts exergy to heat, but it does so based on the rules of energy transfer and the dissipative structure itself.

As an example of complexity from dissipative structures arising from simple rules, he presents Conway’s Game of Life. There seems to be no limit to the complexity that can arise from these rules. However, these complex patterns can be easily disrupted, showing the vulnerability of this homeostasis.

Properties of Dissipative Structures

-

All dissipative structures consume exergy, transforming useful energy into less useful energy.

-

All dissipative structures give rise to complexity (i.e., they are self-organizing) as an emergent property of the way their inherent rules channel their energy flows.

-

No dissipative structure is immortal

Crises can disrupt homeostasis. The more complex a system is the more possibility of a crisis occurring as well a crisis causing a cascade of further crises ultimately unraveling homeostasis.

Assuming a dissipative structure has access to unlimited exergy and no crises, can it go on forever?

“In general no, because they are never static and never go backwards. No natural process is reversible in itself, because entropy always increases, never spontaneously decreases. The same processes that brought a dissipative structure must continue, because energy must continue to flow, increasing complexity. Each increase in complexity has a metabolic cost. As these costs accumulate, eventually the system becomes unsustainable on its energy base and increasingly fragile. At some point, a crisis occurs and there’s a complexity collapse. If exergy is still available post-collapse, new dissipative structures will arise anew, typically with significant differences from the old structure.”

The biologist Eugene Odom describes this process in ecosystems called ecological succession. Ecosystem means a biological community of interacting organisms and their physical environment. An ecosystem begins on pure rock with small and simple dissipative structures. Eventually the entire ecosystem collapses and ends. An ecosystem begins on pure rock. A new ecosystem is built on a previous ecosystem. Each community in the ecosystem alters the environment. “It culminates in a homeostatic ecosystem in which biomass and symbiotic function between organisms are maintained. Maximum that is per unit of energy flow. Nature always optimizes. To repeat, self-organization is directed towards achieving as large and diverse a dissipative structure within the limits set by the available energy input and the prevailing physical conditions. Once homeostasis is achieved, the ecosystem is mature. However, eventually the ecosystem succumbs to its own fragility. A small perturbation in climate, or a fire, or an evolution of a disruptive, invasive, or parasitic species, and all the intricate specializations that lead to the optimization of the structure become in turn the cause of the system’s failures. In the long view, this is not a tragedy, but an essential component of the evolutionary process. It’s precisely the story of life on this planet with its breathtaking diversity not only across continents, but across time.”

Eventually, every organism relies on the whole system to survive. Once the system dies, the individuals die as well.

What about civilization as dissipative structures?

Energy Return on Investment (EROI)

EROI = (total energy acquired) / energy spent to acquire energy

EROI for most creatures is between 1 and 2. An EROI less than 1 is starvation. An EROI towards 2 means growth.

The EROI of hunter-gatherer societies is roughly 1.5. Just enough to form kinship groups, reproduction, and the fastening of a few tools and decorations. The cultural complexity can be impressive, but the social connections are necessarily limited.

Social connections tend to track closely with EROI. Agricultural settlements tend to have an EROI of 4, allowing specializations within the societies not directly related to energy gathering. Complex tools could be developed. Stored food also helps to preserve energy.

Communities tended to over-exploit an agricultural area resulting in reduced yields over time, reducing EROI. Second, successful communities were an inviting target for raiders. This contributed to a second leap in complexity to agriculture-based empires. These empires tend to have an EROI of 6. Empires tend to have a boost in EROI after conquering other settlements, either over-exploiting them or continuing to slowly extract resources. This created highly complex hierarchies and specializations.

However, after all surrounding settlements are conquered they must be administered and garrisoned, taking energy. Diminishing returns set in with settlements being further apart and EROI declines. To combat a declining EROI, taxes tend to increase on agricultural outputs and inexorably leads to resource depletion. Finally, the weakened empire is conquered or falls to pieces.

Example, Rome. The Ancient Roman Empire was especially good at running an empire. Conquest temporarily increased EROI by a factor of 2, but each attempt they made to maintain increased the cost of homeostasis. Only excessive taxation could maintain the metabolic cost of empire. Resource depletion (including human resources) eventually led to permanently declining EROI and complexity (including economic, social, and political/administrative) collapse.

He cites Joseph Tainter’s work Collapse of Complex Societies.

“According to Tainter’s Collapse of Complex Societies, societies become more complex as they try to solve problems. Social complexity can be recognized by numerous differentiated and specialised social and economic roles and many mechanisms through which they are coordinated, and by reliance on symbolic and abstract communication, and the existence of a class of information producers and analysts who are not involved in primary resource production. Such complexity requires a substantial “energy” subsidy (meaning the consumption of resources, or other forms of wealth).

When a society confronts a “problem,” such as a shortage of energy, or difficulty in gaining access to it, it tends to create new layers of bureaucracy, infrastructure, or social class to address the challenge. Tainter, who first (ch. 1) identifies seventeen examples of rapid collapse of societies, applies his model to three case studies: The Western Roman Empire, the Maya civilization, and the Chaco culture.

For example, as Roman agricultural output slowly declined and population increased, per-capita energy availability dropped. The Romans “solved” this problem by conquering their neighbours to appropriate their energy surpluses (in concrete forms, as metals, grain, slaves, etc.). However, as the Empire grew, the cost of maintaining communications, garrisons, civil government, etc. grew with it. Eventually, this cost grew so great that any new challenges such as invasions and crop failures could not be solved by the acquisition of more territory.”

There were no resources left with to rebuild, fertile soil, harvestable forests, and stable human communities. Further developments in energy capture were limited before the industrial age. Capturing mechanical energy improved, but nothing to increase EROI above about 5.

The invention of the combustion engine and acquisition of fossil fuels to produce the heat changed everything. Coal and later oil gave an EROI of 100. One unit of energy in, 100 units of energy out. A seemingly limitless energy use to create incredible complexity. The result is what we have today.

Globalized Industrialized Civilization occurs at EROI > 20. Putting this into perspective, a healthy adult can sustain about 75 watts of energy for 8 hours. That’s about 600 watt hours of work, 0.6 of a kilowatt. 10 people working together can produce 6 kilowatts a day. A gallon of gasoline can propel an automobile 30 miles in 30 minutes.

How long would it take you to push your car 30 miles? How many friends would you need to help you?

An average American consumer directly and indirectly uses enough energy daily to consume the work of hundreds of people. This energy imbalance sustains our global civilization and lifestyle.

The Challenges We Face

- Our civilization is designed for high energy flows.

- The quantity of fossil fuels remaining on Earth is dwindling

- The less fossil fuel that remains, the more it costs to exploit

- There are no substitutable energy sources that have a high EROI

- Our non-energy resource base (minerals, water, arable land, etc.) is also dwindling

- The ecological basis of any future low-EROI civilization is being destroyed

EROI goal of 20? Because there isn’t much difference between an EROI of 20 compared to an EROI of 100.

We’re falling off the “energy cliff.” Greater extraction of energy needs infrastructure like paved roads, decreasing EROI of oil to 30. As the easy to access oil was used up, smaller pockets with cruder oil were found and extracted at greater cost. By the start of the 21st century, the EROI for oil was 20. The EROI of the smaller pockets of oil are 10 or less.

Wind and solar are now competitive with oil at the point of generation, but if we need to store the energy, the EROI becomes 1. Unconventional oil sources become an EROI of less than 5. Arable land becomes too precious to use on bio-fuel.

Established empires have metabolic costs. A reduction of 5% of metabolic costs means the empire must cannibalize and use its reserves.

Scrambling back from the Energy Cliff

- Exploit existing energy sources at a faster rate

- Use the existing energy sources more efficiently

- Make the existing economic and social orders less energy intensive

- Find new energy sources to replace existing ones

He argues none of these are possibilities.

Increasing fossil energy production?

- We can’t exploit oil further due to low value of the remaining oil.

- Coal use can be increased but only at severe environmental cost even before climate change is considered, and that supply too will peak before long

- Shale oil, recovered through fracking, already has too low of an EROI to make it profitable to extract

- Continuing to release green house gases at our present rate, let alone an accelerating rate, puts the planet on track for global extinction by climate change in one to two decades, that will probably result in near-term global extinction of most life, including us. Carbon capture and sequestration technologies to mitigate this are unproven, and certain to reduce the EROI of fossil fuels to 1 or less if widely implemented

Increasing Efficiency

- We’ve dramatically increased efficiency already. Yet for every efficiency introduced, the rate of consumption has increased, not decreased. This is called the Jevons Paradox, and it is an observable feature of natural economies. In the absence of forced rationing, efficiency always increases rather than decreases the rate of consumption.

- Increasing efficiency requires the development of new technologies: new kinds of motors and devices, new lighting technologies, etc. New technologies require research, prototyping, and then capitalization in the marketplace, and each of these steps demands an energy budget. Moreover, there are diminishing returns on innovation, so each new increment of technical progress requires more energy, on average, than the ones that came before, and the rate of increase is exponential.

He gives the example of patents in the early days compared to patents now. Edison, Tesla, and others got the low hanging fruit. Rarely in current times are patents awarded to single inventors but go to research groups of dozens of people on a team.

The 4 Primary Energy Sources

Solar, nuclear, tidal, geothermal.

Fossil fuel isn’t an energy source, it’s an energy carrier, like a battery. The battery can be recharged but only over geological time periods of hundreds of millions of years, not for humans.

Geothermal and tidal hasn’t been exploited meaningfully because the engineering challenges are too great to make it economical.

Nuclear energy, in principle, is ideal. Because of the cost in producing and deconstructing fission nuclear plants and the enormous risks involved, no nuclear plant has stood on its own economically. Most rely on subsidies. Few countries are still exploring this option because crises can and do occur.

Nuclear fusion wouldn’t have these problems, but it’s been feasible for 40 years or so and still hasn’t been developed.

Liquid fuels (bio-mass) cannot replace other fuels with our current needs. The batteries to carry the energy requires lithium, which is abundant but energy intensive to recycle. A battery like this in your car could weigh several hundred pounds. There’s enough lithium available to replace the engines of every car in the world once.

For a car, we can recharge the batteries and make this feasible. However, freights and other large vehicles cannot sustain this. Trains can be converted as they run on electricity, but currently the generators run on diesel. In Europe and Japan, they’re wiring their trains to avoid diesel, but nothing is being done for American infrastructure.

Hydrogen? Hydrogen is an energy carrier and has an energy efficiency of 30%. The real difficulty is in transportation with dangers like explosions. Example, Hindenburg disaster.

The entire petroleum based transportation infrastructure needs to be converted to an electricity base. The cost would be several times the cost of any previous industrial initiative in human history, and we have to do it while at the same time reducing our overall energy use.

A big problem is having energy on demand. To maintain the grid without fossil fuels means the generating capacity must be higher than the average demand, and the excess energy must be stored when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing.

Numerous studies show this increases the cost per watt by an order of magnitude, i.e. by a factor of 10.

Embodied energy is in everything we buy. On average, one calorie of food delivered to you requires 10 calories of energy from fossil fuels. In other words, the EROI of food in our society is 1/10th. 10 units of energy in to get 1 unit of energy out. Replacing this system with liquid fuel increases the cost beyond the reach of nearly everyone. What is true of food is true of nearly every commodity, from the house you live in to the socks on your feet.

There are replacements for fossil fuels, but not for this society.

Can we go back?

Can we have a neo-modern version of society with 19th century energy use?

Our food has changed in its biological function to be dependent on fossil fuels with fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides.

There is a solution: wide-scale, local, distributed farming. However, living off the land is very difficult without engines and pesticides. We also need a change in social priorities and cohesion.

He says we’ve seen the climax of our society.

The collapse is already underway.

We use the word ‘economy’ equivocally. There’s the material economy (the production, movement, and use of energy, including raw materials) and the financial economy (the system used to track and facilitate the material economy). In an economy that’s in balance with its energy flows, the financial economy closely parallels the material economy and provides useful services like rational pricing, mitigation of risk. Another essential service is using excess resources to facilitate increased energy flows in the material economy and make growth possible.

A universal symptom of complex civilization collapse is the financialization of growth. The material economy shrinks while the financial economy grows, creating financial bubbles. Since 2008, incomes have declined while the stock market has tripled. He argues that billionaires don’t have billions of dollars in the material economy. Our income relates to rent, food, and daily life. However, billionaires money relates to power. He’s not against the revolution, but it’s a mistake to think we can solve world hunger with “monopoly” money.

In real terms, the economies of wealthy countries all went into permanent decline between 1970-1990. Emerging economies like China and India fueled massive growth based on coal and on the demand of manufactured goods from wealthy countries. The emerging economies have also peaked, and the material economy is shrinking. Governments responded by inflating the GDP.

They put things in the GDP like inflated rent. If you own your own home, they impute rent paid. It has nothing to do with the material economy. Banks have been financing to keep this all afloat at the cost of increasing individual debt.

Populations of vertebrates have declined by 60% since the 1970s. Land vertebrates, insects, fish, are all becoming extinct at an accelerating rate. There is no material economy for humans if the ecosystem collapses.

“The science is now crystal clear. We’ve got at best 10 years to ween ourselves off fossil fuels, or we’ll see at least 4C of additional warming possibly as soon as 2040, possibly by 2080, with no means whatsoever to bring the planet back to equilibrium.”

Feedback loops at that point could boost warming 10C more. Ecosystems would collapse, and there would not be a resource base for new civilizations to form. If this civilization were to continue another 20 years, it would mean omnicide. It’s fortunate indeed that it cannot. The first step in enjoying the end of the world is knowing any hope in maintaining the current system is delusory, not by technology, renewable energy, nor political revolution will save us from complexity collapse. Step 2, he doesn’t think any predictions of how collapse will play out in the short term are useful, it’s too chaotic.

There are worse outcomes than collapse. If we use our weapons of mass destruction, the outcome is not collapse but apocalypse.

Even if New York were optimally farmed, it could only sustain 21% of the current population. To survive, we need a new way of thinking and a new way of being. He says that doomsday preppers and ultra-rich will learn a hard lesson. The aim is to build something better.

The ecologist C.S. Holling developed the adaptive cycle of ecosystems. There’s a cycle of creation, destruction, and renewal. Each of these is necessary for the development of life. With increasing complexity, the system becomes less able to adapt and change. That system becomes liquid energy for new life.

And then he goes into a positive outlook on change.

Humanity: The Final Chapter

Dr. Sid Smith has another great talk from a year earlier in early 2018.

We began overshooting, going into ecological debt, in 1970.

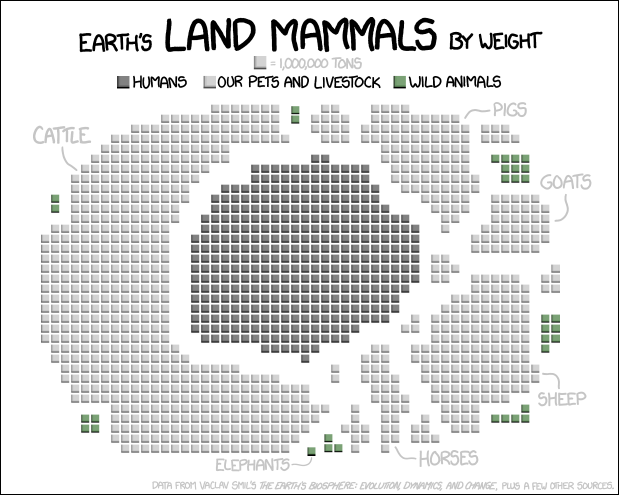

A great XKCD comic to visualize land mammals.

What Changed My Mind About Climate Change?

MAY 21, 2019

This guy was in a libertarian think tank and initially rallied against thinking climate change would be devastating. He uses the perspective of risk management and investing to show why we should take climate change very seriously and change policy.

Unfortunately, no analogy is precisely applicable to the climate debate. We have a great deal of historical data, for instance, to inform our sense of the likely distribution of potential outcomes in the finance sector. We have many fewer data points to repair to in the course of informing our sense of the distribution of potential outcomes in the climate arena. We have imperfect geologic records. We have imperfect computer models, which reflect our imperfect understanding of climate dynamics. But that ambiguity is itself a motivating factor for reducing emissions. Never before have we run an experiment where greenhouse gases were loaded into the atmosphere at today’s rates. We have no backup planet if things go horribly wrong. When asked why I changed my mind about federal climate policy, this is a large part of my answer. Building an argument against climate action upon a forceful claim about the most likely outcome of greenhouse gas emissions is to build an argument upon analytic sand. You don’t have to believe with all your heart that the worst-case scenario is sure to happen. You just have to understand that it is one possible outcome. And that we should not be making policy based on an assumption that we are certain of this or that outcome. When it comes to managing large-scale risks, straight-forward economics suggests that we ought to take climate change very seriously.