“The Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay diet, or more commonly, the MIND diet, combines portions of the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet and the Mediterranean diet.[1] Both the DASH diet and the Mediterranean diet have been shown to improve cognition; however, neither were developed to slow neurodegeneration (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease).[2] Therefore, a team at Rush University Medical Center, headed by Martha Clare Morris (a nutritional epidemiologist), worked to create the MIND diet.[3] Like the DASH and Mediterranean diets, the MIND diet emphasizes the intake of fresh fruit, vegetables, and legumes.[4] The MIND diet also includes recommendations for specific foods, like leafy greens and berries, that have been scientifically shown to slow cognitive decline.[3] Recent research has shown that the MIND diet is more effective at reducing cognitive decline than either the Mediterranean or DASH diets alone.[3] Additional testing has shown that the level of adherence to the MIND diet also impacts the diet’s neuro-protective effects.[5]” - via Wikipedia

Abstract from Nutrition and risk of dementia: overview and methodological issues.

“After little more than two decades of research on nutrition and dementia, there is strong evidence for preventive effects of vitamin E, B vitamins, and n-3 fatty acids, and deleterious effects of saturated fat, on dementia. Among specific foods with evidence of neuroprotection are green leafy vegetables and other vegetables, berries, and seafood. A number of studies have examined dietary patterns, particularly the Mediterranean and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets; neither of these diets is tailored to the specific foods and nutrients that have been identified as neuroprotective. A new diet, called MIND (Mediterranean–DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay), incorporates many elements of the Mediterranean and DASH diets but with modifications that reflect the best evidence for brain neuroprotection. The evidence in support of the relation of various nutrients and the Mediterranean diet to dementia has been inconsistent. The seeming inconsistencies may be explained by inattention to nutrient/food intake levels in the interpretation of study findings and trial design. This includes a shifting metric among studies for scoring adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Future studies should pay particular attention to levels of intake in the design and analyses of nutritional studies.”

Keywords: diet patterns, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive decline

Conflicts of interest

“The author declares no conflicts of interest.” -

Very readable version from the author’s university.

“One of the more exciting things about this is that people who adhered even moderately to the MIND diet had a reduction in their risk for AD,” said Morris. “I think that will motivate people.”

Morris and her colleagues developed the MIND diet based on information that has accrued from years’ worth of past research about what foods and nutrients have good, and bad, effects on the functioning of the brain over time. This is the first study to related the MIND diet to Alzheimer’s disease.

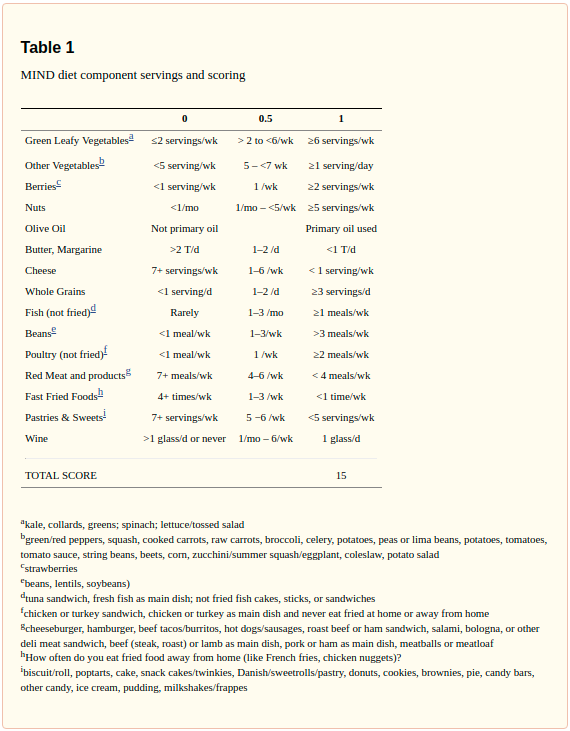

The MIND diet has 15 dietary components

10 “brain-healthy food groups:”

- Green leafy vegetables

- Other vegetables

- Nuts

- Berries

- “Berries are the only fruit specifically included in the MIND diet.”

- Blueberries

- “Blueberries are one of the more potent foods in terms of protecting the brain,” Morris said, and strawberries have also performed well in past studies of the effect of food on cognitive function [university article].

- Beans

- Whole grains

- Fish (not fried)

- Poultry

- Olive oil

- Wine

The 5 unhealthy groups are:

- Red meats

- Butter and stick margarine

- Cheese

- Pastries and sweets

- Fried or fast food

“The factors that play into individuals’ neurocognitive development to peak intelligence may or may not be the same as those that cause neurodegeneration,” Nutrition and risk of dementia: overview and methodological issues.

However, the MIND diet uniquely specifies green leafy vegetables and berries as well as servings of food components that reflect the nutrition–dementia study findings. Among the different types of vegetables, the green leafy variety has been identified as having the strongest protective effects against cognitive decline.42–44 In the Rush Memory and Aging Project, the rate of decline among those who consumed 1–2 servings per day was the equivalent of being 11 years younger in age compared with those who rarely or never consumed green leafy vegetables.44 Green leafy vegetables are rich sources of lutein, folate, vitamin E, beta carotene, and polyphenols, nutrients that have been related to brain health. Prospective epidemiological studies of dementia do not observe a protective benefit from the consumption of fruits in general.42,43,45,46 Dietary intakes of berries, however, have been demonstrated to improve memory and brain neuroprotection in multiple animal studies47 and to slow cognitive decline in the Nurses’ Health Study.48 However, certain food components and servings of the DASH and Mediterranean diets are not included in the MIND diet because there is a lack of evidence for their importance for brain health, including high consumption of fruits (3–4 servings in both the DASH and Mediterranean),41,49 dairy (DASH),49 and potatoes and high fish consumption (2 servings/day and 6 meals/week, respectively, in the Mediterranean diet41). The MIND diet recommends one or more fish meals per week on the basis of prospective study evidence that this frequency is sufficient to lower dementia risk and that there is no additional benefit evident from higher servings per week.50–52 The MIND diet does include many other food components of the DASH or Mediterranean diets, including extra-virgin olive oil, nuts, whole grains, and low-fat sources of protein, such as legumes and poultry. - Nutrition and risk of dementia: overview and methodological issues.

It is important that the findings of protective relations of the MIND diet score and cognitive decline are replicated in other cohort studies to confirm these associations. To establish a causal relation between diet and prevention of dementia, a diet intervention trial is required. Modifications to the MIND diet score would be expected as new foods and nutrients are identified from scientific advances in the field of nutrition and brain neurodegeneration, a field that is currently underdeveloped.

Use of absolute levels of intake of foods and food categories has several advantages over relative cut-offs based on within-population levels of intake. First, findings across studies are more interpretable when they have a common metric. Second, important information about the optimum level of brain benefit for different dietary components becomes known when the data are analyzed and presented in terms of servings per day across different studies in different populations. And third, the scientific findings on optimum nutrition for brain health can be more easily translated to the general public when framed in terms of servings per day. One advantage of the MIND diet score is that the scoring for each dietary component is based on absolute as opposed to relative levels of intake. For many of the dietary components (e.g., seafood, vegetables), the intake levels required for optimum scores were based on direct scientific evidence for brain health. For other dietary components (e.g., whole grains, poultry), direct evidence for brain health is lacking and optimum scores are based on the cardiovascular disease literature.

MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging

In this community-based study of older persons, we investigated the relation of diet to change in cognitive function using an á priori-defined diet composition score (MIND) based on the foods and nutrients shown to be protective for dementia. Higher MIND diet score was associated with slower decline in cognitive abilities. The rate reduction for persons in the highest tertile of diet scores compared with the lowest tertile was the equivalent of being 7.5 years younger in age. Strong associations of the MIND diet were observed with the global cognitive measure as well as with each of five cognitive domains. The strength of the estimated effect was virtually unchanged after statistical control for many of the important confounders, including physical activity and education as well as with the exclusion of individuals with the lowest baseline cognitive scores.

However, the MIND diet uniquely specifies consumption of berries and green leafy vegetables, and does not specify high fruit consumption (both DASH and Mediterranean), high dairy (DASH), high potato consumption or greater than 1 fish meal per week (Mediterranean). The MIND modifications highlight the foods and nutrients shown through the scientific literature to be associated with dementia prevention…Studies of fish consumption observed lower risk of dementia with just 1 fish meal a week with no additional benefit evident for higher servings per week. Thus, the highest possible score for this component of the MIND diet score is attributed to one or more servings per week…Fish are a rich source of long-chain n-3 fatty acids which have been shown to reduce Aβ formation and oxidative damage, and to increase synaptic proteins and dendritic spine density.

The study findings are supported by a number of strengths including the prospective study design with up to 10 years of follow-up, annual assessment of cognitive function using a battery of standardized tests, comprehensive assessment of diet using a validated questionnaire, and statistical control of the important confounding factors. Another important strength is that the MIND diet score was devised based on expansive reviews of studies relating diet to brain function.

A limitation of the study is that the dietary questionnaire had few questions to measure some of the dietary components and limited information on frequency of consumption. For example, a single item each provided information on consumption of nuts, berries (strawberries), beans, and olive oil. However, this imprecision in the measurement of the MIND score would tend to underestimate the diet effect on cognitive decline. Another limitation is the self-report of diet which some studies suggest can lead to biased reporting in overweight and cognitively impaired adults. Concern that biased diet reporting could explain the findings is mitigated by the fact that statistical control for factors like obesity, education, age, and physical activity had no impact on the estimated MIND diet effect and the association remained strong in analyses that omitted the participants with MCI and whose diet scores changed over the study period. Further we observed no modification in the effect by level of these potential confounders.

The primary limitation of the study is that it is observational and thus the findings cannot be interpreted as a cause and effect relation. Replication of the findings in other cohort studies is important for confirmation of the association, however, a diet intervention trial is required to establish a causal relation between diet and prevention of cognitive decline. Further, the findings were based on an old, largely non-Hispanic white study population and cannot be generalized to younger populations or different racial/ethnic groups.

The MIND diet is a refinement of the extensively studied cardiovascular diets, the Mediterranean and DASH diets, with modifications based on the scientific literature relevant to nutrition and the brain. This literature is underdeveloped and therefore, modifications to the MIND diet score would be expected as new scientific advances are made.

From the Harvard review wine is no longer required and alcohol can be removed entirely. Simple guidelines are:

“The healthy items the MIND diet guidelines suggest include:

- 3+ servings a day of whole grains

- 1+ servings a day of vegetables (other than green leafy)

- 6+ servings a week of green leafy vegetables

- 5+ servings a week of nuts

- 4+ meals a week of beans

- 2+ servings a week of berries

- 2+ meals a week of poultry

- 1+ meals a week of fish

- Mainly olive oil if added fat is used

The unhealthy items, which are higher in saturated and trans fat, include:

- Less than 5 servings a week of pastries and sweets

- Less than 4 servings a week of red meat (including beef, pork, lamb, and products made from these meats)

- Less than one serving a week of cheese and fried foods

- Less than 1 tablespoon a day of butter/stick margarine”